Reading the Movies

The Dancing Image has encouraged its readers and fellow bloggers to share the film-related books that have had a special significance for them. The original poster encourages the tagging of five friends to do the same; I won't, since it always seems like a guilt-trip if you happen to be too busy to participate. Let us just say you're free to join in if you want to. At any rate, here are my picks:

The Dancing Image has encouraged its readers and fellow bloggers to share the film-related books that have had a special significance for them. The original poster encourages the tagging of five friends to do the same; I won't, since it always seems like a guilt-trip if you happen to be too busy to participate. Let us just say you're free to join in if you want to. At any rate, here are my picks:In the Blink of an Eye by Walter Murch. A friend of mine lent me his copy some years ago, which I read from cover to cover in one sitting and promptly ordered my own copy shortly after. Murch's film editing credits include Apocalypse Now, Godfather Part III and Cold Mountain. His book is probably the single best volume I have ever read on what a film actually is, and how an audience responds to it psychologically and emotionally.

Unfiltered: The Complete Ralph Bakshi by John M. Gibson and Chris McDonnell. This sumptuous, coffee table-styled volume has a sentimental meaning for me, because Mr. Bakshi signed my copy when I got to meet him at a gallery event in Soho. Moreover, though, this is an incredible, career-spanning scrapbook full of animation artwork, and a sometimes hyperbolic but always sincere and passionate biography of one of America's most misunderstood and underrated film artists.

Cult Movies by Danny Peary. One of the finest collections of film criticism essays that I own. Peary uses "cult" as a pretty broad umbrella term, reviewing Casablanca, The Searchers and The Wizard of Oz alongside fare like Two-Lane Blacktop and The Honeymoon Killers. His Freudian reading of King Kong, wherein Kong is the manifestation of Carl Denham's sexual frustration a la the Id Monster in Fordbidden Planet, is one of the most fasctinating I've ever read. Like all of my favorite critics, Peary's writing says just as much about him as it does the films in question.

Making Movies by Sidney Lumet. A real gift of a book: one of America's finest filmmakers candidly sharing his experiences from a storied career. This book details the nitty-gritty experience of directing, the importance of each aspect of production, and instructions on how to use every single tool in the filmmaker's toolbox to better tell your story. A must-read for anyone interested in getting into the business.

Hollywood Babylon by Kenneth Anger. And speaking of books by respected filmmakers... while Anger enjoys a reputation as one of the fathers of the post-modern cinematic language, his famous written work is really little more than enjoyable, mud-caked load of the famous and the dead's dirtiest laundry. Every grain should be taken with a grain of salt and simply enjoyed. More than anything, this is a secret-handshake book for cinephiles, something that automatically starts conversations when people see you reading it on the subway. Did I also mention that it's just a hell of a lot of fun?

Gilliam on Gilliam, edited by Ian Christie. I got this as a birthday present when in my early teens, when Terry Gilliam and Tim Burton were my greatest cinematic idols. Gilliam is remarkably candid here and recalls his career and his many battles with producers and studio chiefs with great clarity. It's a fascinating portrait of a very neurotic but highly intelligent and creative artist.

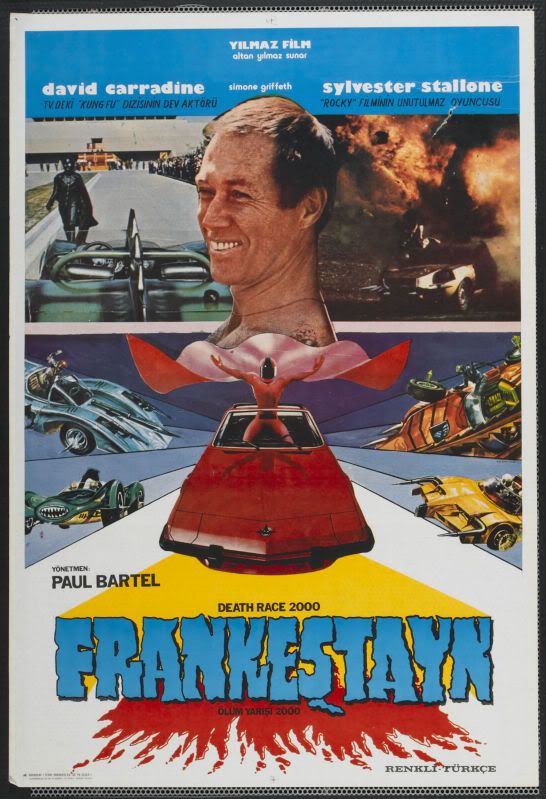

The Psychotronic Video Guide by Michael J. Weldon. The most tattered and battered book on my shelf, this is the Leonard Maltin guide's black sheep brother. No B-movie (or A-film with B-ish roots) is left unreviewed, from horror to blaxploitation, martial arts and grindhouse pictures of all kinds. Though most video guides of this nature have been rendered obsolute by IMDb, this book is still probably the only place you'll find any info a great number of unloved genre pictures.

Hitchcock/Truffaut, by Alfred Hitchcock and Francois Truffaut. When one great, young filmmaker interviews an even greater, older one, the results are one of the finest film books ever committed to print. Hitchcock starts off very joke and anecdotal but eventually starts to probe deeply into his own work and his methods of working. An indespensible volume.