Happy Birthday Quentin Tarantino! (and me.)

Quentin Tarantino and I share the same birthday - and I think that is pretty cool. Coming to terms with the fact that I myself am a Quentin Tarantino Fan is something that took several years and a lot of introspection. As with being labeled a Star Wars Fan, there is a lot of "dork baggage" that comes with such a label, and people make assumptions about you based upon it, but utlimately, you've gotta go from the gut and like what you like. As Luis Guzman says in Boogie Nights, "wear what you dig," well, I think a similar philosophy applies to watching what you dig. And I dig Mr. Q.

There's no doubt that Tarantino ushered in the contemporary era of (supposedly) auteur-driven cinema, as well as inspiring a wealth of less-brilliant pictures featuring gangsters, guns, and clever dialogue. There's also no doubt that he borrows liberally from older films, but if you ask me, there is a lot more to his pictures than a movie dorkical parlor game of "spot the reference." Every obscure karate picture or unheard-of Italian giallo slasher that Tarantino name-drops is of personal significance, and in my opinion, the chief among the director's finest skills is his ability to mix the fantasy and artifice of cinema with the beautifully observed nuance of real life.

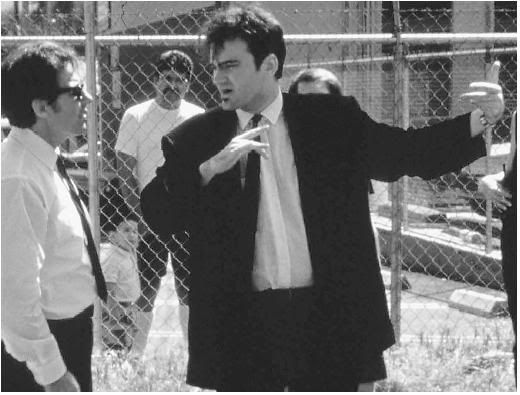

The opening scene in the diner in Reservoir Dogs is a beautiful example of this. Although the Maddonna speech has probably been quoted by nerds more frequently than the entire scripts of Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Star Wars, and The Big Lebowski combined, this still does not detract from its quality. Here are eight guys all duded up like Jean-Paul Belomondo, but they talk and act exactly like working-class guys. They aren't "going over the plan" one more time like criminals do in every single other heist picture you've ever seen - they're taking a well-earned break before their big day. They look like they stepped out of a French New Wave film, but they talk like a bunch of construction workers. What's more, the social status of each member of the group, how well they know or don't know each other, is perfectly established even before we're shown their flashback scenes.

Death Proof, Tarantino's second segment of Grindhouse, confused and put many off, including myself, after I first saw it. Watching it directly after Robert Rodriguez's pus-splattering zombie extravaganza Planet Terror it felt almost like a practical joke - forcing the audience to calm their asses down and try to focus on a chitchat-heavy stalker flick, for which most of the duration Kurt Russell's killer Stuntman Mike lurks in the background while groups of women banter back and forth about relationships, their favorite gearhead movies, and other assorted topics. It was only after watching the expanded version of the picture on DVD that I really wrapped my head around what a wonderful, personal, and even somewhat autobiographical film it is.

When Stuntman Mike rattles off his list of shows and movies he's worked on as a stuntman, only to be be faced with the blank stares of the local hipsters in the Texas Chili Parlor who have never heard of any of them - one can't help but imagine that Mr. Tarantino had many similar one-sided conversations about about obscure pop culture before he became a hot-shit movie director. And then there is the exchange between Eli Roth's character and his dweeby companion about getting the girls drunk on Jagermeister so that they can take advantage of them - a scene which seems like filler in terms of its relation to the plot, but thematically it is quite central to what Death Proof is all about. These two are meant to be regular, all-American joes - not sociopathic killers who get a chubby off of crashing into young women in a souped-up automobile - and yet their plotting and scheming comes off as almost as sinister. Tarantino seems to be suggesting, rather scary notion that it is, that there is a little tiny bit of Stuntman Mike inside every man.

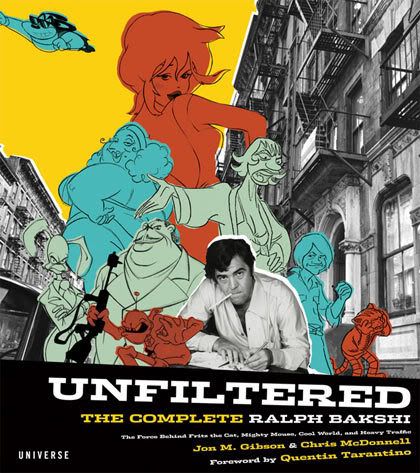

I know many people who have beef with him as a taste-maker: people become interested in things like surf music and old grindhouse movies just because of him, and I think people feel a lot of bitterness, like he personally taking ownership for these things. I never saw him taking ownership so much as sharing the things he loves - and the guy really does love a lot of movies. He's clearly not limited in his love for 70's b-films, if you've ever heard him talk about Rio Bravo, the guy said he considered Howard Hawks a father figure through watching his movies, because he never had a real one. I read a wonderful New York Times article a while back in which he sings the praises of an obscure Roy Rogers vehicle, The Golden Stallion. The man's taste and knowledge is seemingly boundless (aside from Martin Scorsese and possibly Joe Dante, I can't think of any other director more film-smart), but coming from a background of being these wonderful, dear-hearted dorks you find all the time working in video stores, and eventually becoming a celebrated auteur, Tarantino has the unique distinction of knowing films first, and people second. True to form, once the geek's social skills start to live up to the magnitude of his artistic, entertainment and pop-cultural knowledge, he becomes unstoppable.

Jackie Brown, which Tarantino liberally adapted from Elmore Leonard's novel Rum Punch, has long been my favorite of his films, and it's interesting to hear the director talk about that film retrospectively, as it seems he doesn't care for it as much as his original stories. I love the film for its Hawksian scenes of downtime and characters hanging out - there is a sense of loneliness and quiet desperation that seeps through every frame, and its heist plot is placed on the back burner in favor of character exploration. The nagging fear of growing old alone is very present in this film, probably more than Tarantino would like to admit, or maybe even more than he actually realizes. And personally, I've always found great artists entirely capable of creating art that was About Something (capital A, capital S) and not actually be aware of it; after all, John Ford insisted all throughout his life that his films were nothing more than solid western adventure yarns, and anyone who thought there was anything to try and read into them was a effeminate, latte-drinking, Frenchified pinko.

Kill Bill and Pulp Fiction are two films I find myself not revisiting as often as the aforementioned three, but despite them being the most prominent examples Tarantino's detractors hold up for reasons to knock him (he's an empty reference-chucker, he gets off on violence, he's just a big overgrown toddler who's seen two many grindhouse movies and needs to take a walk outside), I think there is still a great deal of introspection and depth here. In Pulp Fiction, the notion of the gangster hierarchy is dismantled beautifully. The biggest, baddest sons-of-bitches aren't the mob bosses on the top of the food chain, who, although they live a life of crime, they still live by a somewhat ethically slanted moral code - the real ones to look out for are the mouth-breathing rednecks, the itchy-trigger-fingered knuckleheads, and the young punks who think they're hot shit: these are the ones who are truly threatening, because they have no moral code whatsoever. Also, like reservoir dogs, it beautifully blends real-life minutia with tried and true genre trends. In Tarantino's universe, a Mexican standoff in a hotel room is moderately thrilling, but what's really exciting is how his two hitmen characters will manage to clean up their blood-stained car before their connection's wife gets home and sees the mess.

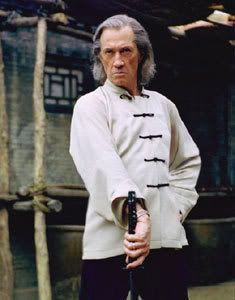

The operatic Kill Bill is a different animal. We first see Uma Thurman's Bride as a blank slate of scorned anger. We cheer her on slashes her way through Japanese Yakuza Land, Shaw Brothers Kung Fu Land, Spaghetti Western Land, and Gritty Rape-Revenge Flick Land, the same way Pee-Wee Herman is chased on his bike through the various sets on the Warner movie lot, uninhibited by our bloodlust, because we know that after each of the film's extras got their limbs chopped off and shed their respective bucketloads of fake blood, they got up back up again once the director yelled 'cut' and helped themselves to a donut from the caterer's table. But Tarantino turns us on a nickel at the end of his epic, when it is revealed to the Bride that her daughter is alive and living with the man she has sought to kill. Like Pinocchio's transformation into a real boy, she stops being a blank slate of scorned-woman badassery and becomes a flesh and blood being, a transformation so powerful that she utterly breaks apart.

So happy birthday Mr. Tarantino: for marrying the personal and the universal, the artificial and the incredibly real, for your generosity in sharing so many obscure and neglected older films and filmmakers, and just in general, for being a gateway drug and a starting point for many young filmmakers like myself. Many happy returns.